Hmong American Experience in Burke County

Overview

Burke County is home to a significant population of people who immigrated from Thailand, Laos, Vietnam, and Cambodia. While each country represents people groups with unique cultures, a majority of the immigrants from Southeast Asia are part of the Hmong ethnic group. North Carolina has the fourth-largest Hmong population in the US.

A political refugee group that started immigrating to the US in the late 1970s, the Hmong were the CIA’s frontline soldiers in the “Secret War”, the Lao theater of the Vietnam War. Originating around the Yellow and Yangtze River Deltas in Southern China, Hmong history and diaspora are marked by three large exoduses.

The majority of the Hmong people left Southern China in the 18th century due to persecution and immense social and economic pressure by Imperial China. They re-settled in the mountainous regions of Southeast Asia, mainly in the Xieng Khouang Province in Laos and the future site of the CIA’s largest paramilitary operations against the North Vietnamese’s communist forces and the Pathet Laos – the pro-communism group that assumed control after the US departed Laos in 1975.

The Hmong left Laos and braved the treacherous crossing of the Mekong Delta into Thailand after their US allies abandoned them. Those lucky enough to make it into the refugee camps were screened for potential placements in other countries; 90% resettled in the US while others went to Canada, France, and Australia.

Re-settlement in the US – the Hmong were resettled into dense metropolitan areas in California, Minnesota, and Wisconsin. Many clans moved around the country to re-establish kinship and live among family.

In the early 1990s, to get off government assistance, many Hmong began looking for jobs. Unable to apply their rural lifestyle to their new metropolitan homes, many started looking to re-settle on the east coast. North Carolina was an attractive option due to a large number of jobs in textile and furniture. Additionally, the beautiful mountains were a peaceful lure to those who missed Laos. Today, there are over 10,000 Hmong in Western North Carolina. A large majority have settled in Morganton, Hickory, and the Charlotte area. Today, the Hmong people in Burke County work in all industries from manufacturing, healthcare, and the trades. They are also business owners and entrepreneurs.

FOR A DEEP DIVE INTO THE ASIAN AMERICAN WEALTH GAP, click here.

The Story Cloth | An Evolving Tradition

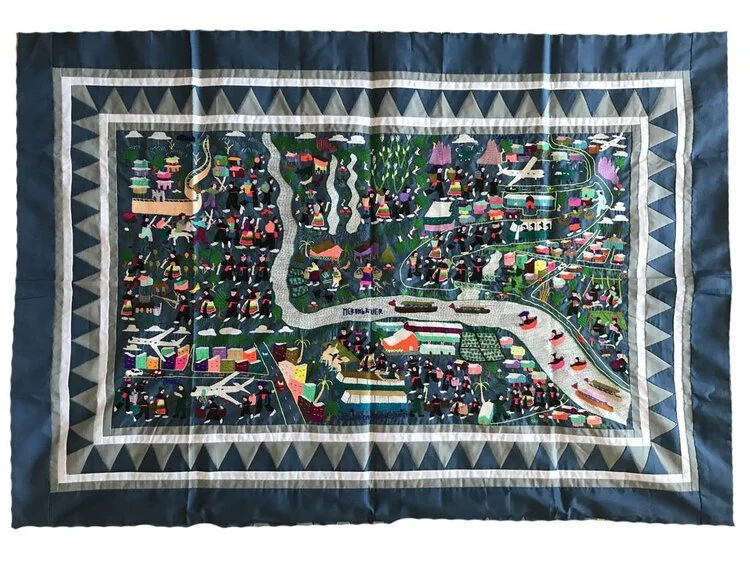

Ka Ying Yang’s story cloth, made in Thailand by an unknown refugee, circa 1970

As a migratory people, the Hmong traditionally invested in craft that complimented their mobility, such as paj ntaub (pronounced pondouw), or flower cloth. This art form was produced through intricate needlework such as appliqué, reverse appliqué, embroidery, and batik on clothing and other fabrics. These articles were cherished and played an important roles in rituals and rites of passage.

Story cloths developed out of this tradition, illustrating the Laotian Civil War (also known as the Secret War) beginning in 1953. These tapestries chronicle the conflict along with the subsequent genocide, resistance, exile, and immigration of the Hmong to the United States.

Mai Lo Chang: Details

MA thesis project by Katy Clune, completed for the Folklore Program, Department of American Studies at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill in May 2015.

“While in the refugee camps, I ran a cooperative group of 7-8 sewers that created these story cloths and then we would split the profits equally. Originally, these intricate stories were drawn and sewn and then sold by refugee women to make money to support their families. They have become vivid, historical pieces that detail the Hmong exodus out of Laos, life in the Thai refugee camps, and our journey to the US.”

—Ka Ying Yang, 2019

Ka Ying Yang’s story cloth, made in Thailand by an unknown refugee, circa 1970

A Woven Story

Story cloths often depict these events:

Long Tieng (also spelled Long Chieng, Long Cheng, or Long Chen) as it appeared from 1967-1974, under operation by the CIA,

The flight of the Hmong from Laos into Thailand across the Mekong River

The refugee camp at Vinai

Hmong people studying English at Phanat Nikhom

Their arrival and departure from a Bangkok airport

Ka Ying Yang’s story cloth, made in Thailand by an unknown refugee, circa 1970

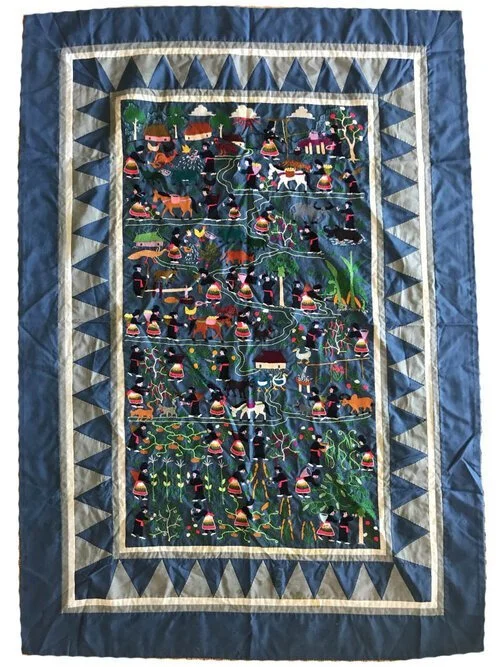

“I bought this from a lady in Fresno, California about 20 years back. She had purchased it from someone in the refugee camps. I love how it depicts our lives in Laos - we were farmers and grew rice, corn, and many fruits and vegetables. It was a community effort to survive in Laos and so we relied heavily on exchanging labor.This story cloth is a piece of Hmong history that I treasure dearly.”

—Mai Lo Chang, 2019

Hmong Culture In Burke County | As seen through…Tea Yang

Tea, Values and Culture Manager for The Industrial Commons.

One of the greatest personal achievements of my life has been to be able to share my story as a former Hmong refugee. I am only here and thriving because of my parents’ love, courage, and sheer determination to escape war and persecution. This is my love letter to them.

One of my earliest memories of Laos was as a two-year old singing in a field of poppy flowers, the plant the Hmong used to produce opium for medicinal purposes as well as a cash crop to pay taxes. I remember nonchalantly eating the poppy seeds and then being sick for a week! Another memory was of my two older sisters arguing while our parents were away at the farm. The eldest took me and left for our grandmother’s hut, leaving the other sister behind. Scared and alone, she followed us; however, she was too small to reach the latch to lock the door so she left it open. When my parents returned home, they found our chickens and pigs inside our hut gobbling up the year’s harvest, including all of the rice, sugar, salt, and smoked meat. To this day my sisters still argue about who was at fault, even though neither can remember what they were arguing about in the first place.

We are Hmong, an ethnic minority that lived high up in the isolated mountains of Laos and have cultivated a unique knowledge of the land, including the Ho Chi Minh trails. During the Vietnam War, the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) used these trails to filter supplies to their troops in South Vietnam. Unable to effectively repel the NVA in this rough terrain, the CIA saw the Hmong as an ally due to their knowledge of the geography and a fiercely independent spirit that detested communism. In 1963, without Congress or the American public’s knowledge, the CIA recruited the Hmong into Special Guerilla Units (SGU) that were tasked with 1) disrupting the NVA’s supply lines by direct engagement, and 2) rescuing American pilots who were shot down while bombing these trails. This paramilitary operation was the largest the CIA had ever conducted up to that point and became known as the Secret War. Towards the end of the war, the total loss of the Hmong population was as high as 30%, including 30,000 - 40,000 soldiers and 2,500 - 3,000 declared Missing in Action. Due to the high loss of Hmong men, boys as young as thirteen were being recruited into the SGU.

In 1973, the US signed a ceasefire with Vietnam; however, fighting would continue until 1975. By this time the communist forces had taken root in Laos and a civil war raged on with the Hmong caught in the middle. The CIA evacuated top Hmong military personnel, but left the majority of civilians behind to fend for themselves. When Laos fell to communism, the persecution of the Hmong began due to their alliance with the US. Many hid in the jungles for decades, braved the treacherous journey across the Mekong River to Thailand, or submitted to communist rule to avoid being sent “re-education” camps.

My family chose to brave the journey out of Laos. We spent months in the jungle, eating whatever we could forage, and were constantly hunted by soldiers. Many people lost their lives on the way and entire groups were double-crossed by guides they had paid to get them to safety. We finally made it to Thailand in 1987 and lived in three refugee camps before immigrating to the US in 1989.

We were resettled in Fresno, California and survived on welfare and the generosity of the surrounding churches. Unable to find jobs and unfamiliar with urban life, my parents were attracted to North Carolina because of the mountains and the plentiful manufacturing jobs. We moved to WNC in 1993 and have been here ever since. They toiled away relentlessly and purchased their home in 1995, giving us a sense of stability for the first time in our lives despite the many challenges along the way.

Today, we have a large, loving, and boisterous family. I am the third oldest of eight children, and a proud auntie (my favorite role) to 11 nieces and 11 nephews. Family time can be absolutely chaotic because the kids outnumber the adults; but, every now and then, I glance over at my parents to study their expressions amid the chaos. I see absolute joy, pride, happiness, and infinite love radiating through their eyes. To get to this point, it took unimaginable courage, resiliency, and an unwavering resolve to protect what they love the most in this world - their children.

For a deeper dive into the Hmong of North Carolina

Tea with family, Laos, 1985, Photo Credit unknown

Tea & family, Chiang Kham Refugee Camp, Thailand, 1988, Photo Credit unknown

Tea & sisters UNHRC photos, Chiang Kham Refugee Camp, Thailand, 1988, Photo Credit unknown

Tea's mom in re-education classes, Phanat Nikhom Refugee Camp, Thailand, 1988-1989, Photo Credit unknown

Tea, mother, sister, aunt and son, veteran, Chiang Kham Refugee Camp, Thailand, 1988, Photo Credit unknown

Tea, dad, sister, Chiang Kham Refugee Camp, Thailand, 1988, Photo credit unknown

Tea's dad in re-education classes, Phanat Nikhom Refugee Camp, Thailand, 1988-1989, Photo Credit unknown

Yang Family Farm, Lincolnton, NC, 2012, Photo Credit Tea Yang

Tea & parents WPCC graduation, Morganton, NC, 2011, Photo Credit unknown

Tea & parents at graduation at UNC-CH, Chapel Hill, NC, 2014, Photo Credit Pa Yang